Evolution of Sinsemilla: The Origins of Modern Cannabis

If you were born any time after 1990, then you may not know that cannabis used to be a stemmy, seedy mess. It often looked like someone had mowed their lawn and stuffed the clippings in a bag. Seeds outweighed actual flower, and much of it was a dreary brown color. Cannabis everywhere used to be like this — until sinsemilla changed everything.

What is Sinsemilla?

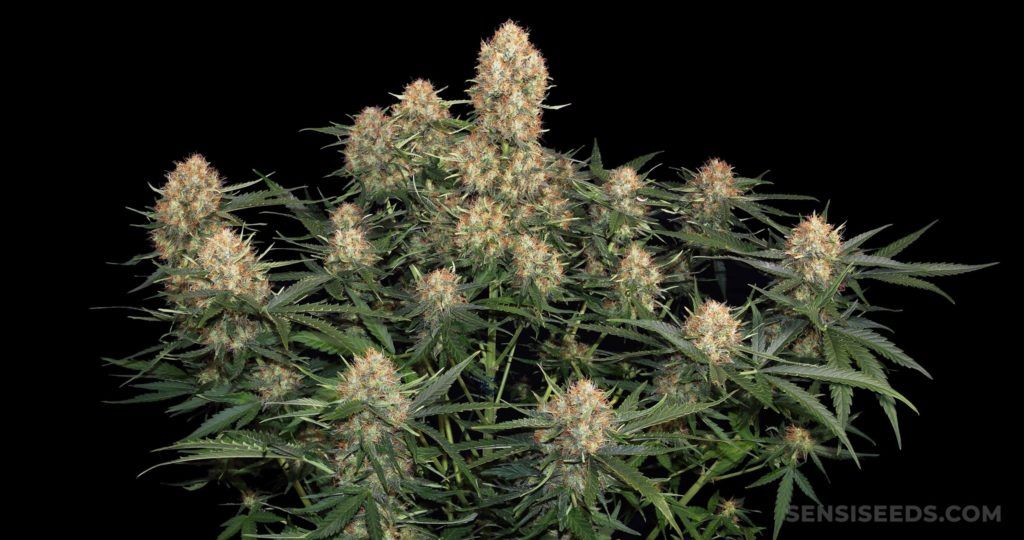

“Sinsemilla” means without seed. It’s the seedless cannabis we know today, created by isolating female plants from males. Without pollination, the female plants produce dense resin glands in a futile attempt to attract pollen. For us, that resin means high THC and the frosty buds that revolutionized the cannabis experience.

Origins

No one knows exactly where the practice began. Most believe it started in Southeast Asia, where cannabis has been used for millennia. The same concept has long been used in brewing hops for beer. But the modern sinsemilla we recognize today seems to trace back to the highlands of southern Mexico.

Genetic Innovation

By the 1970s and ’80s, breeders in the U.S. and Holland began crossbreeding landrace varieties with sinsemilla techniques, creating legendary strains like Skunk No. 1, Haze, and Northern Lights. These became the backbone of the global cannabis gene pool.

- Original Haze came from Central California, later taken to Holland in the 1980s, blending Colombian, South Indian, and Thai genetics.

- Northern Lights, from the Pacific Northwest, incorporated Skunk and Haze and spread widely by 1980.

Even today, nearly half of Dutch seed company strains contain Skunk No. 1 genetics

Lasting Impact

Sinsemilla didn’t just improve potency — it redefined cannabis culture. The practice paved the way for today’s legal market, where potency, terpene profiles, and breeding innovation continue at an exponential pace.

And that, in a nutshell, is the evolution of sinsemilla.

ADDITIONAL RECENT POSTS